Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Everywhere we look, there are mentions of artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and their implications for the future. News stories and social media feeds predict a heyday of ease and comfort as we assign more and more mundane tasks to technology (the art that accompanies this post was created by AI). In contrast, we’re also given the dark prophecies of Asimov and Bradbury come to life: When our computerized creations become so sentient that they can resent us, how will we control them?

More realistically, however, people are rightfully concerned about their jobs: Cashiers are already becoming obsolete, data entry by remote workers is becoming a relic, and countless other positions previously filled by people are slated to go extinct in the next few years. How, then, do we reckon with this revolution?

As the father of two older boys, one in college and one about to go there, I’m relieved that both of them have chosen irreplaceably human endeavors for their futures: One is in theatre, and the other plans to pursue architecture. These are professions that AI will never be able to fully usurp. After all, theatre is among the humanities, a select group of art forms and practices marked by their innate reliance upon authentic emotion and genuine experience. Our hamartia, the human condition, is ironically our greatest strength when it comes to livelihoods that are AI-proof. Architecture will be helped by AI, certainly, but to design and create livable spaces that consider the needs of complex people, we need human minds and hearts. Ask AI to design a mid-20th Century ranch house like the one on The Brady Bunch, and you’ll probably get a reasonable facsimile. But ask AI for a blueprint of a home that considers the individual needs of 21st Century family members, and confusion results — the blinking cursor begins to smoke.

As a teacher, I’ve already encountered the challenge of getting students to write rather than use ChatGPT or some similar product. For now, AI-generated writing is fairly easy to spot: Its reliance upon certain words and phrases, its preference for sterile-sounding language, and its occasional errors about obvious matters all make it detectable, even without running an essay or paper through an online checker or two. Combine those facts with a vast divergence from a student’s in-class writings, and AI use becomes obvious. But we know that technology consistently advances, and as time elapses, the fakes will become harder to spot, especially as classrooms become more tech-dependent. This is why some teachers and professors have gone back to old-school blue books, those lined-paper pamphlets of an earlier era, for class writing. And while I see the nostalgic appeal and hard-nosed devotion to justice driving such a practice, I also see its inherent temporary nature. Returning to number two pencils and canary yellow legal pads may get us by for a while, but students, parents, and clients of the new age won’t tolerate this Luddite approach for long. We need to find the middle ground between total AI reliance and achieved, owned learning quickly. Compromises like “You may use an AI editor for the writing you have authored independently in class” serve as a good start. This technique prepares students for the world to come without damaging their acquisition of knowledge. Further, they learn by seeing the corrections made by QuillBot, Grammarly, and other language-fixers. And if these products make a mistake as they sometimes do, so much the better. That’s where the real learning begins — technology has never been and will never be infallible, and the sooner students grasp this truth by experience, the better off they will be.

As a poet, I’m not worried about AI. I’ve seen the replica-poems it produces, and while some sound good on the surface, a closer look reveals that same artificial shimmer visible in the art that I’ve used above. Something’s missing; there’s a bad aftertaste like that of saccharine diet sodas from the seventies. An astute reader can tell that the cane sugar of the human touch is missing from this thing’s formula, whatever it may be. The “experiential resonance” — the sense that an event or product is organic — just isn’t there. Call it instinct if you will, but a reasonable human being can tell the difference between the things we do and make and the contrived, data-driven simulacra of thought-approximating algorithms. An initial, superficial “Oh, that’s lovely!” soon becomes an “Oh, this isn’t what I thought it was.” And that kind of deflating disappointment will toll the end of our infatuation with AI. Like any other once-novel discovery, this, too, will lose its luster.

So, what’s the big picture? The AI “scare” is similar to that of Y2K: Yes, we should consider it, but no, it isn’t Armageddon. As we prepare and adapt, we will add it to our toolboxes, become indifferent to it, and move on. Just as we healed the hole in the ozone layer, just as we eliminated acid rain, and just as we defeated diseases of long ago, we will coexist with this latest change until it no longer seems intriguing or threatening. We could easily theorize a future dystopia like those seen in science fiction, but it’s more likely that balance will prevail as it always has. For parents, teachers, and creators, AI is nothing to obsess over. Put simply, it’s just another thing. And if history has taught us anything, it’s that things are perishable.

As World Poetry Day arrives (today!), and National Poetry Month waits just around the corner (April), I thought I’d offer a brief missive on literary matters both personal and universal:

Most people are poets to one degree or another, though some don’t like to admit it. When you walk outside and feel the temperature in the morning, your response to it is the beginning of poetry. The texture of the air on your skin, the combination of sunlight, birdsong, and environmental noise, and the state of the world around you (your seasonal lawn, the road nearby, the leaves that have fallen on your driveway)…these things are the earliest signals that your mind wishes to celebrate life by composing a poem. Most people immediately shut down this impulse with negative self-talk: “I’m not a poet,” or “That’s what somebody else would do,” or “That stuff’s too deep for me.” The truth is, we all want to record and respond to the world around us in artistic words; some folks just lean into that longing more than others.

There’s also that dreaded mental reservation called imposter syndrome. “I don’t know enough/haven’t done enough/can’t compete with experts” hinders so many earnest efforts. Nobody is the greatest at something the first time they try it, and there are plenty of metaphors and parables extolling the virtue of practice and patience. Being unwilling to try something because of initial frustration is ordinarily a child’s reaction, but in the adult world, too many creators quit before they’ve properly begun. Nowhere is this fact more evident than in poetry — the persistent thrive, even if they aren’t that great.

I won’t name names here, but walk into your mainstream bookstore and you’ll find the one shelf called a “poetry section” filled with poorly designed and badly written tomes by people whose greatest claim to fame is that they’ve penned trite cliches or radical malarkey for the last 25 years or more. And those “books” are placed alongside Dickinson, Shakespeare, and Frost. This literary injustice is a turnoff to those who may be considering writing well-crafted verses of their own, and it should be. But this sad fact should also be a motivator for producing better work for our current age. Make poetry great again!

So, how do we overcome a closed mindset regarding poem writing? The first step is to get inspired. Sometimes a little help can go a long way, and toward that end, I recently began a new mini-workshop by mail called “Metacreativity: The Process Behind the Poetry.” In this monthly letter, I offer one poem of mine, the backstory behind it, and the process it went through before becoming its final version. Sometimes seeing into someone else’s creative process inspires others to use their own, and this little communication allows readers to do exactly that. I also include a more traditional poetry prompt in every letter, and sometimes I add a QR code that links to an audio recording of the monthly poem. I also include news about my upcoming appearances, book signings, and other events when appropriate.

I’d love to add more subscribers to my growing roster for Metacreativity. Now more than ever, we need fresh voices putting more relevance into our world through poetry. And as celebrations of poetry begin in this first quarter of 2025, I hope you’ll join me in spreading good words. Whether it’s buying a fresh book of poetry or trying your hand at a sonnet, spring is a perfect time to appreciate beautiful language.

As the age of screens and endlessly blinking text continues, there is a need for a return to the gracious, studious, and considerate world of letters. That’s right, the kind that come in your physical mailbox. You get to hold in your hand an artifact — a piece of living history sent to you by someone who cared enough to share with you something about their life. That’s why I’ve abandoned Substack altogether in favor of a new, better, more human alternative: StampFans.

Using this service, I will be able to send you, my subscriber, some rich insights on poetic life. Each month, you will receive a letter that contains one of my poems, an explanation of its inspiration, and some details about its actual creation (number of drafts, materials used, etc.). I’ll also be including announcements about upcoming publications, appearances, workshops, and similar engagements. As a teacher, I’d love to receive something like this from my favorite poets. I’d use it in my classroom regularly, and I hope other educators feel the same way.

While I’d hoped that my presence on Substack would be as successful and meaningful as my time on WordPress has been, I’ve learned the hard way that the audience for poetry is much more receptive to personal, physical communication than it is to just another online presence. With this in mind, please subscribe to my StampFans so that you too can receive good news, good reading, and something more uplifting than junk mail. I promise that your modest investment will be richly rewarded. I eagerly await your subscription, and I can hardly wait to share this window into my work with all my WordPress family! Thank you in advance for your support of Metacreativity: The Process Behind the Poetry .

Recently, two poet friends of mine expressed an interest in completely giving up on all things literary. Their latest poems were consistently rejected, they weren’t inspired to create new work, and frankly, they weren’t seeing the benefit of engaging in the one thing they previously enjoyed. It happens to us all.

Inspiration isn’t something you can fake; that is, you can’t force a creative epiphany or revelation. But you can create optimal conditions for these kinds of “sparks” to occur. That’s why I created Socratic Journaling in the first place — my students approached the blank page with dread, and they needed a push to get something going. And while simple prompts can often generate work that feels forced or generic, arriving at a subject on one’s own can yield pieces that are authentic and rewarding.

Enter the Socratic Journal — a workbook intended to get people thinking about themselves, their minds, and their experiences. By creating ladders of inquiry, creativity naturally flows from the mind as answers and questions feed off one another. And those questions and their answers often reveal to the writer previously unexplored topics, good for essays, poems, and a variety of other products.

I even had one student, a high school girl, who still claims Socratic Journaling changed her life. It allowed her to think about her own thinking so much that she figured out her issues and personal problems without other helps ( disclaimer: if you are suffering from a serious psychological illness, always consult a professional). But by writing out our thoughts, our big inquiries, and our desires in a systematic fashion, sometimes more than creative inspiration can occur. Knowing ourselves better is a reward of its own.

Whether you’re a writer, a teacher, or simply someone who’d like to learn more about yourself, the Socratic Journal is a wonderful resource to help you get unstuck, both creatively and mentally. Summer is a great time for self-exploration and understanding, and by asking and answering the big questions, who knows what improvements might occur? Give it a try!

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Hello, followers, friends, fans, and family — This is just a quick post to let you know that my latest piece can now be found at The Common (both in print and online):

https://www.thecommononline.org/jesuit-school-fountain-ravens

If you enjoyed this poem, please purchase a print copy of the magazine. They do great work!

The audio clip above is from the sunporch I’ve turned into my own personal writing studio. My family and I moved from our previous home in Riverview (on the outskirts of Tampa) to a new-old place in Carrollwood, one of the historic neighborhoods in the heart of Tampa. The commute to my workplace is shorter, the house itself is smaller (both boys are going off to college in short order, so who needs a big house), and the HOA headaches and zero lot lines are a thing of the past.

We traded all that for history, love, and beauty. As you probably heard in the audio, the new place (built in 1965) is surrounded by bird-filled oaks and magnolias. Their sounds infiltrate the sunporch writing studio every morning as I open the windows, turn on a couple of tower fans, and greet the day with words.

Having just returned from a month-long NEH-funded residency where I studied and wrote about one of my favorite Southern authors, Flannery O’Connor, I’m ready to get back to my usual routine. I loved sitting on the porch of Andalusia (Flannery’s home in Milledgeville, GA), writing poems from a rocker she herself may have written from long ago. But there’s something about abiding in one’s own space and observing personal rituals that helps foster productivity. I’m a fan of beginning the day with cognitive pursuits; geniuses like Frank Lloyd Wright endorse the practice, and I’m a morning person, so it works.

Some of you may have listened to all the birdsong and cicada noise in the audio and thought, “How does he concentrate with all that racket?” Answer: It’s never distracting when the sounds are from nature. At my previous home, my family and I contended with the exhaust-pipe roar of drag racers, the loud feuding of across-the-street neighbors, occasional gunshots, the ceaseless drone of lawn mowers, and the midnight cries of nearby young families’ infants. I may have had my own study at the old house, but to call it that would have been euphemistic at best.

When I compare that tiny square upstairs room to my present place, I have to roll my eyes and chuckle a little. I’ll take Old Florida over new development any day. I can hardly wait to see how this affects my poetry; stay tuned for updates, readers. There’s about to be a golden era of creativity.

The good folks at Salvation South have published a modest piece of creative nonfiction I wrote about the hard times facing my hometown. Special thanks to editor Chuck Reece:

https://www.salvationsouth.com/penny-a-sunshine-state-eulogy-wauchula-hardee-county-florida/

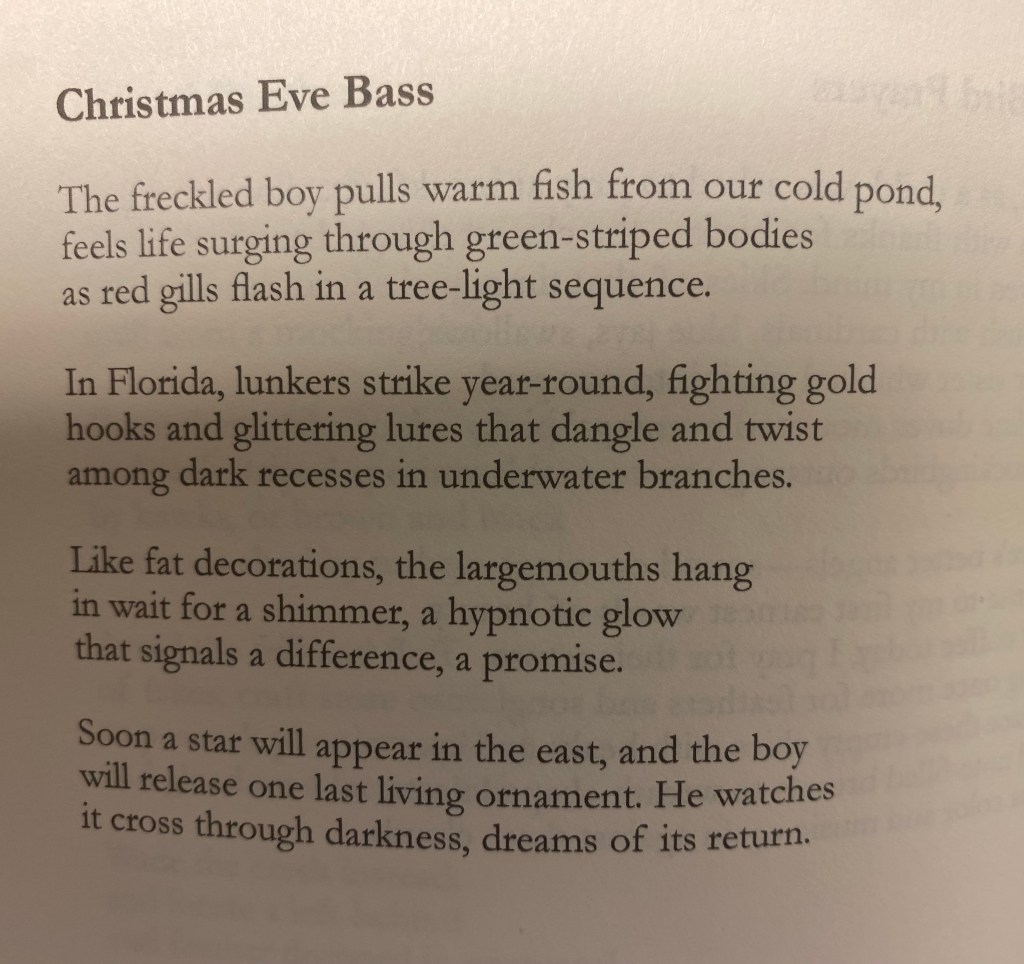

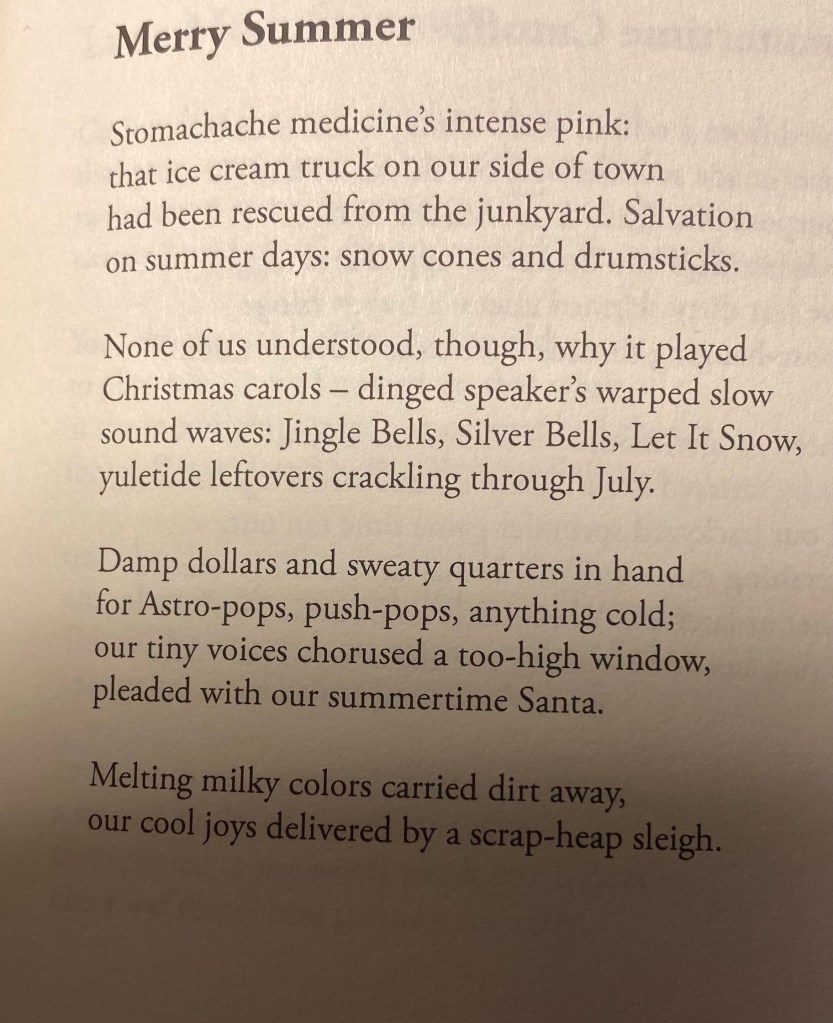

Once in a while at this time of year, workshop participants and seminar attendees express a desire to integrate poetry reading into their holiday celebrations. There’s a fine tradition of reading verses at Christmas get-togethers, and it dates back centuries. As we get more high-tech and less connected to the old ways, events like reading “A Visit from St. Nicholas” can restore in our homes a generational bond, and a continuation or a renewal of tradition.

But we don’t have to limit poems to old standards; even newer poems and those with remote connections to Christmas can have value and add a fun, unconventional event to parties and family gatherings. For this post, let’s look at two poems that could give guests something meaningful and memorable:

Now is also a good time to mention that books of poetry, usually slimmer and more travel-friendly than prose books, make great stocking stuffers. There’s always someone in our circles who is resolving to read more poetry in the new year, and the books linked to above will provide hours of truly engaging reading. Help make a poet’s Christmas brighter, and purchase copies for friends and loved ones! I am grateful to all of you, readers and followers, and I hope this season treats you well.