When I attended the Glen West Writers Workshop in Santa Fe, New Mexico back in 2013, I remember being shocked at the lack of air conditioners. Surely, I assumed, I’m going to roast at night. My charitable hosts told me to keep the unscreened windows open (which my Floridian brain immediately equated with MOSQUITOES), and I’d be more than cool enough. There were trays of lavender in the windowsills to keep out the scorpions. I took them at their word, and sure enough, evening temperatures dropped to a comfortable (even chilly) low, and no insects or lobster-looking arachnids entered. Also, being far out in the New Mexico steppe meant no human intruders tried any funny business.

When I was a boy, my family and I travelled to North Carolina to visit some family members near Highlands. There also, I was told to sleep with the windows open and things would be cool enough. Granted, these windows had screens, but an eager listener could still hear all the nocturnal sounds of the mountains, including owls, rustling varmints, and the occasional stir of trees as breezes came and went. It was one of the most peaceful feelings I recall.

It was not uncommon for me to sleep with my tent windows totally unrolled to expose the screens when I was becoming an Eagle Scout. In Florida, every little whiff of passing air helps tame the intense humidity during most of the year, and a completely zipped-up tent is really nothing more than a sweat lodge. Sleeping with the window flaps down allowed me to see stars and listen for racoons, bears, opossums, or other night visitors in camp. I still slept well, and I remember feeling very close to nature, despite what many would have considered exposure and vulnerability.

Why, you might ask, am I recalling these episodes? The other night, I went to bed without closing my sun porch windows. One would think that such an oversight would result in burglary or other potential dangers. But no, when I came out onto the sun porch the next morning to do a little writing, things were dewy and even a little cool (by Tampa standards), but nothing had been disturbed. The sensation of the porch brought to mind all the other times I’d been allowed to keep windows open at night, and it conjured up an apt metaphor:

In his book From Where You Dream, Robert Olen Butler speaks of writing during that state between sleeping and waking. In other words, write as soon as you get up to tap into that portion of your brain where dreams originate. I believe that the converse of this is also true: When one lies down at night, deflating from the events of a day, the brain begins its filmstrip of previous images and important snatches of things noticed. That is, our “windows are open” in a sense. We are able to vividly piece together disparate ideas by sensing the outside world in a distanced but connected way. Neurologists and psychologists agree, and the emerging brain science behind creativity indicates that people entering or leaving the REM stage of sleep are most capable of allowing the brain to resolve issues the fully conscious mind cannot. This is also why some forms of meditation are effective for helping the mind filter matters down to their essence.

As a writer, I’d like to have my “windows open” all the time. That way, I could channel inspiration and figure out how things are connected more immediately. But to live in such a constantly enlightened state would probably be too sublime — it would remove the challenges that form human experience as we know it. Robert Penn Warren once said, “How do poems grow? They grow out of your life.” Having occasional “windows-open-at-night” moments is satisfactory; too many would make them mundane, not unlike living where you vacation.

For now, I’ll take the infrequent moments of epiphany. They’re what make life as a writer unpredictable and entertaining. And besides, I can’t sleep with the windows open all the time — it’s Florida, after all, and the whisper of A/C and the tick of a ceiling fan have their own certain charms.

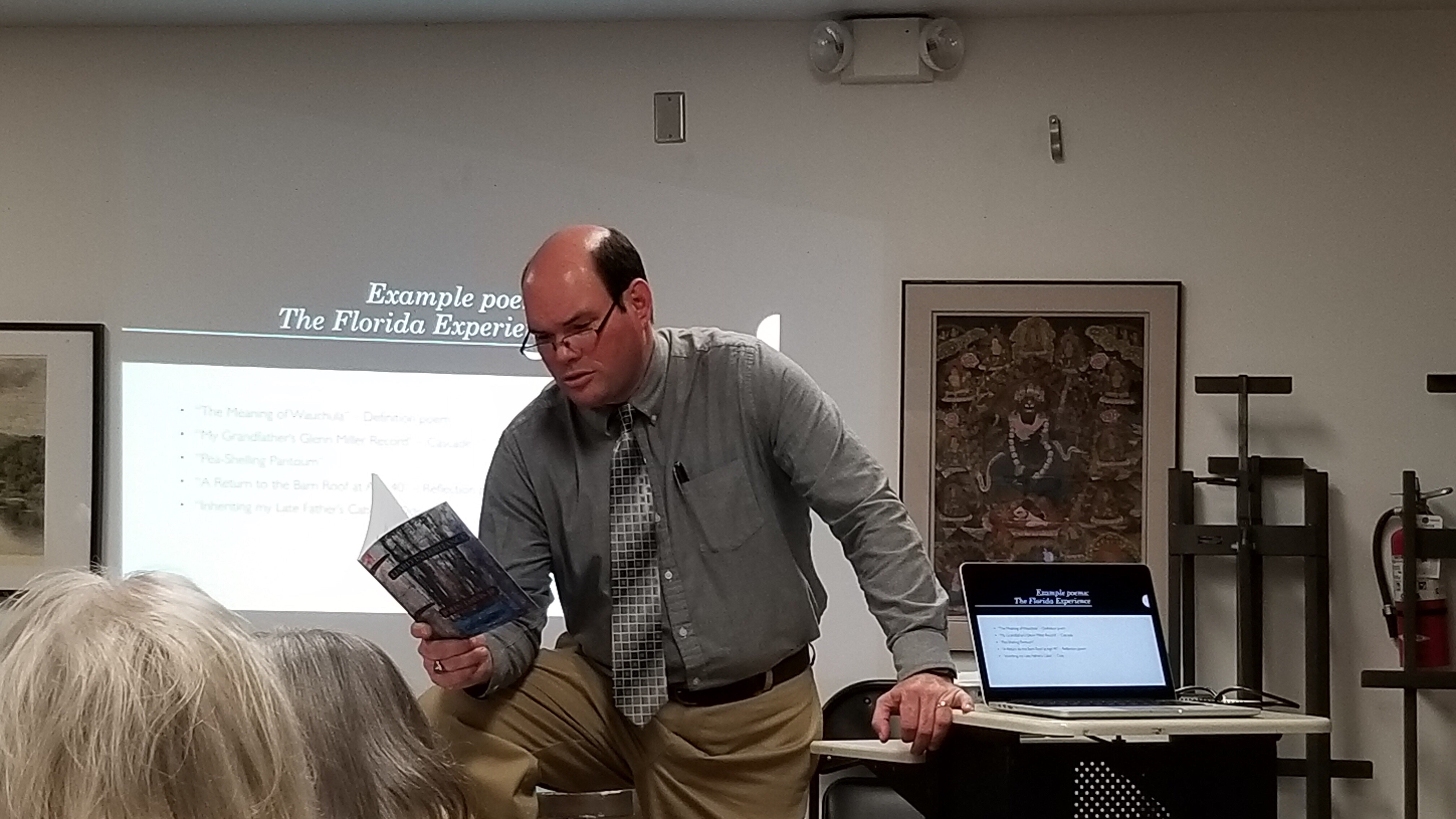

For about six months or so now, I’ve been volunteering for a local arts organization. I’ve provided workshops, seminars, and even the occasional reading. Here’s what I’ve learned: The most rewarding part of being a poet is passing on the joy of writing to others.

For about six months or so now, I’ve been volunteering for a local arts organization. I’ve provided workshops, seminars, and even the occasional reading. Here’s what I’ve learned: The most rewarding part of being a poet is passing on the joy of writing to others.